Toolkit technical background overview

Cybersecurity Toolkit - Introduction

While the World Wide Web may only be 25 years old, cybersecurity attacks have been occurring for more than a century. One of the earliest cyberattacks can be traced back to 1903 when a hacker interrupted a public demonstration of a wireless telegraph machine by sending Morse code insults. Even 100 years ago, hackers were exploiting security holes for the public good. (Dot-dash-diss: The gentleman hacker’s 1903 lulz)

Unfortunately, the world today is very different than it was in 1903. Cyberattacks are no longer being carried out by only script-kiddies and hacktivists attempting to exploit systems for “the good of the public”. The attackers are now governments and well-funded groups who carry out these malicious attacks with the intention to cause real physical and economic harm. And as technology continues to advance, these attacks will increase and become more dangerous. As a result, defending against cyberattacks is becoming ever more crucial for companies.

When looking at the volume of data that can flow through a network, it becomes apparent that using offline, historical analysis techniques are not going to get the job done. While forensic analysis remains a vital part of any cybersecurity solution, modern networks will need to have the ability to analyze traffic in real-time in order to provide meaningful insights immediately.

This is where IBM Streams fits into the picture. By using the Streams platform, companies can perform cybersecurity analysis on their network traffic in real-time. By performing this analysis as the traffic is flowing through the network, companies can filter out the irrelevant data (i.e. the noise) and choose to store only meaningful data. By using Streams in tandem with existing offline analysis, companies will be better able to develop security policies and guard against intrusions.

Given that Streams is an ideal platform for providing cybersecurity analytics, a new toolkit has been added to the Streams 4.1 release called the Cybersecurity Toolkit. This toolkit will provide the building blocks to enable developers and cybersecurity analysts to gain insight into their networks in real-time. In version 1.0 of the Cybersecurity Toolkit, three powerful machine-learning models are being provided:

- DomainProfiling - Detects suspicious behaviour based on profiles built using domains found in DNS response traffic.

- HostProfiling - Detects suspicious behaviour based on profiles built using hosts found in DNS response traffic.

- PredictiveBlocklisting - Predicts whether a domain should be added to a blocklist.

These machine-learning models currently analyze data provided by DNS response records. The rest of this article will provide a high-level explanation of how each of these models work.

Analytics

Domain Profiling

The DomainProfiling operator employs a machine-learning model that analyzes DNS response traffic and reports whether or not the behaviour of the domain is suspicious. This is done by building a profile of the DNS response records over a period of time. At the end of that period, the operator submits a tuple predicting whether the domain that was profiled is “suspicious” or “benign”.

Example

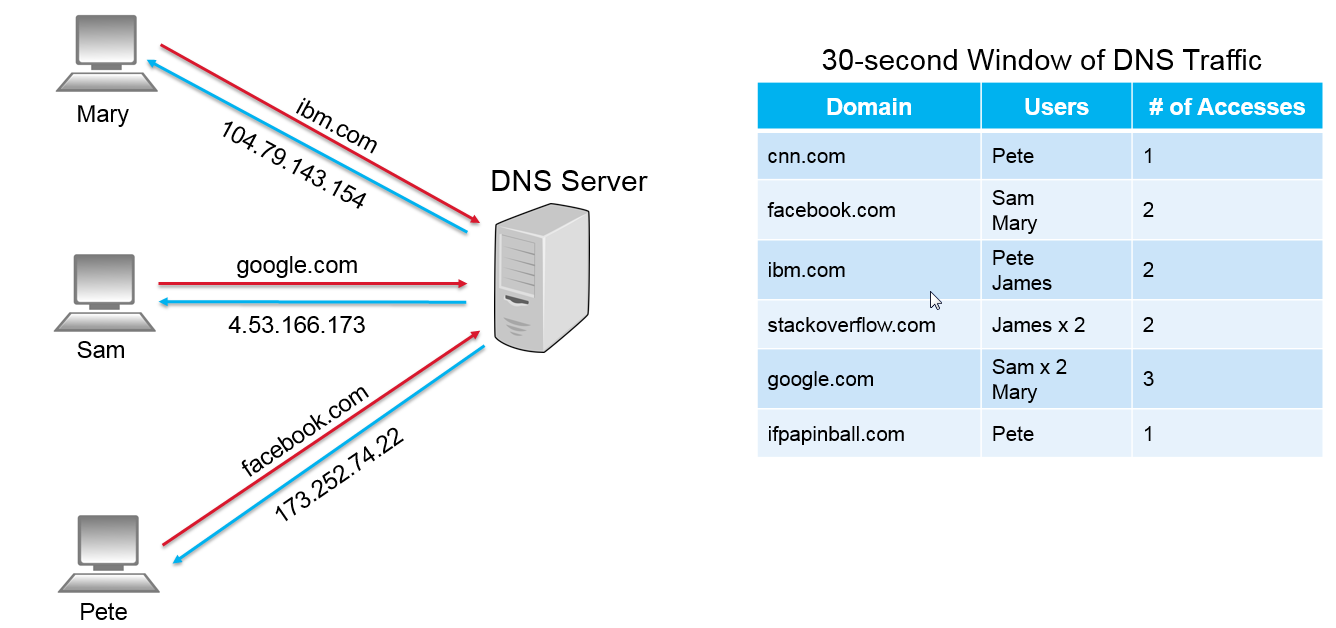

The following example demonstrates, at a high-level, how this process works.

In this scenario, a 30-second window of DNS response traffic was captured. Using this information, a profile was build for each unique domain name. As part of that profile, the number of users that accessed the domain and the total number of accesses for each domain were captured. This scenario is what will be referred to as the “normal” or “expected” behaviour in the network. Each domain was accessed a couple of times in about 30-seconds. In this case, there is nothing out of the ordinary and the analytics are likely to report that each of the domains is “benign”. Now let’s look at another scenario.

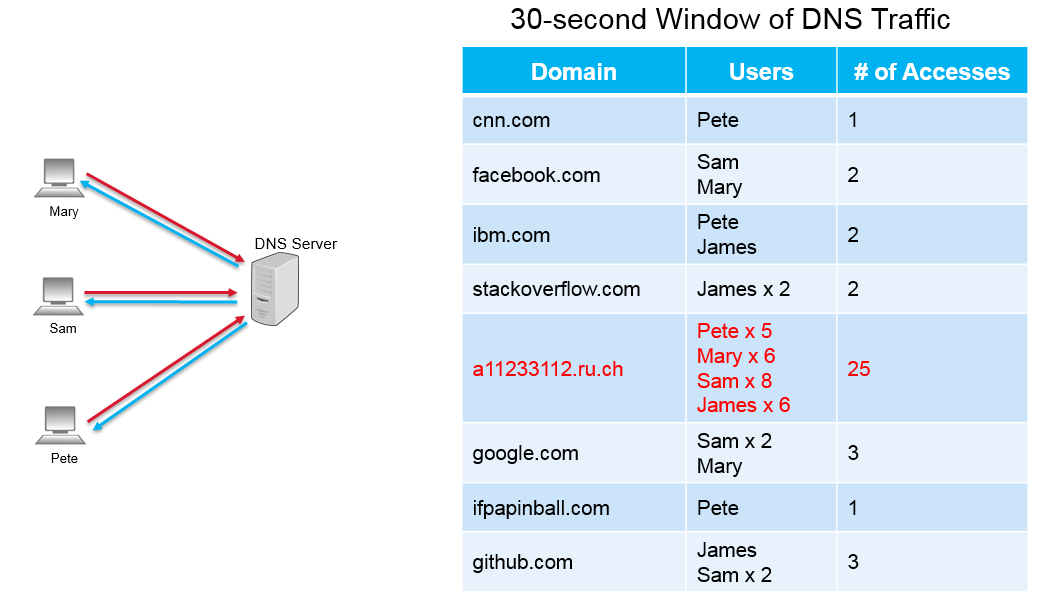

Once again, the above scenario represents a 30-second window of DNS response traffic. However, after building a profile for each domain, a clear anomaly is present. The domain a11233112.ru.ch has been accessed by 4 different users a total of 25 times. Compared to the other domains in the 30-second window, this domain had more than 10 times the number of accesses. In this scenario, the DomainProfiling operator would report this domain as being “suspicious”.

The previous example is intended to illustrate the high-level approach that the DomainProfiling analytics use to determine whether a domain is benign or suspicious. In an actual application, not all DNS response records can be sent to the DomainProfiling operator. There is a specific set of filter criteria that needs to be applied to ensure that the correct data is used in the analysis.

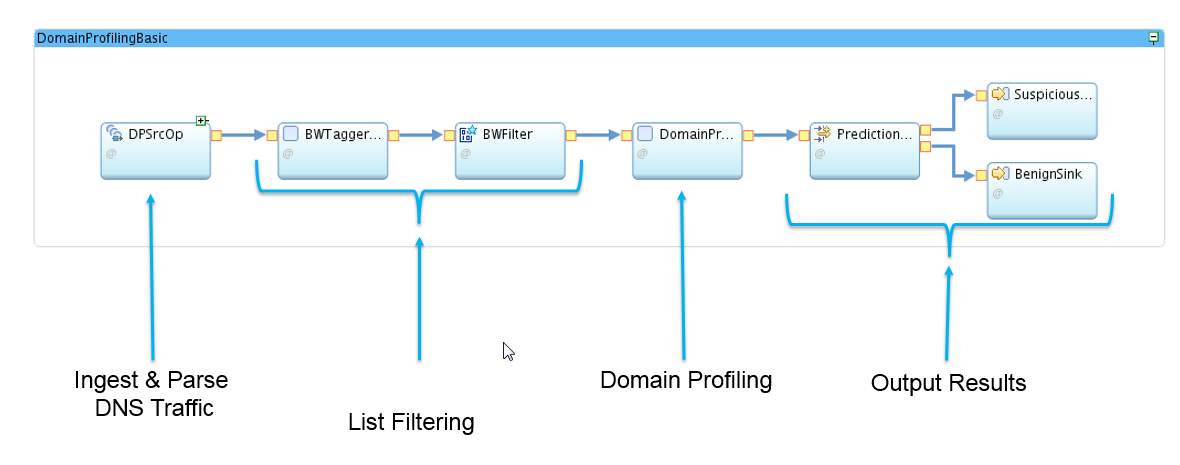

Setting up the specific filters and enrichment criteria can be time consuming. Also, these filters and enirchers need not be changed when developing applications that use this operator. Therefore, rather than expect each developer to implement the same set of static filters and enrichers, starter applications have been provided that include the necessary preprocessing operators. These applications can be extended to allow developers to build custom cybersecurity applications.

Here is a breakdown of the different parts of the DomainProfilingSample application:

Host Profiling

The HostProfiling operator is similar to the DomainProfiling operator, except instead of building a profile for individual domains, it builds a profile for individual users. The HostProfiling operator also employs a machine-learning model that analyzes DNS response traffic and reports whether or not the behaviour of the user (or system) is suspicious. This is done by building a profiling of the DNS response records over a period of time. At the end of that period, the operator submits a tuple predicting whether the user (or system) that was profiled is “suspicious” or “benign”.

Example

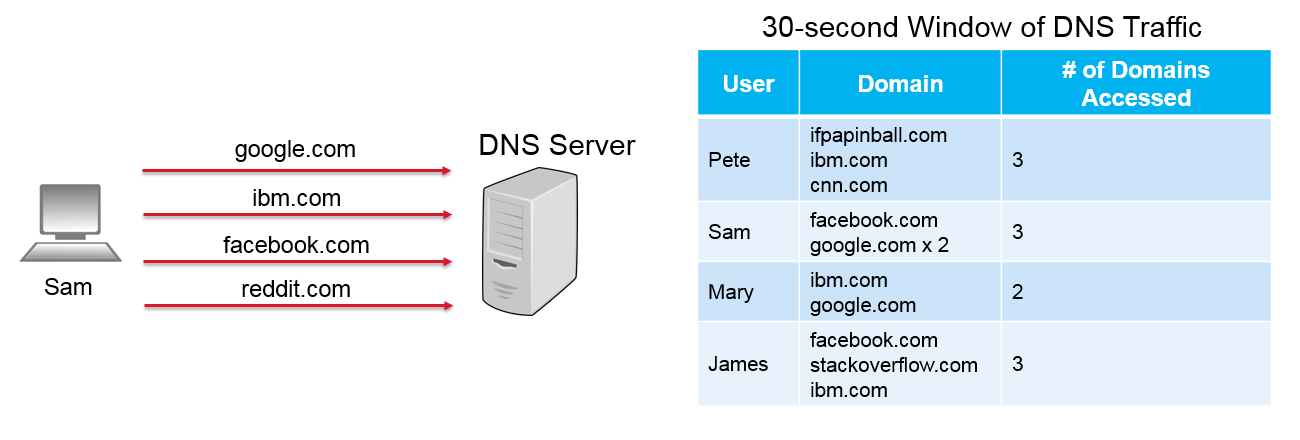

The following example demonstrates, at a high-level, how this process works.

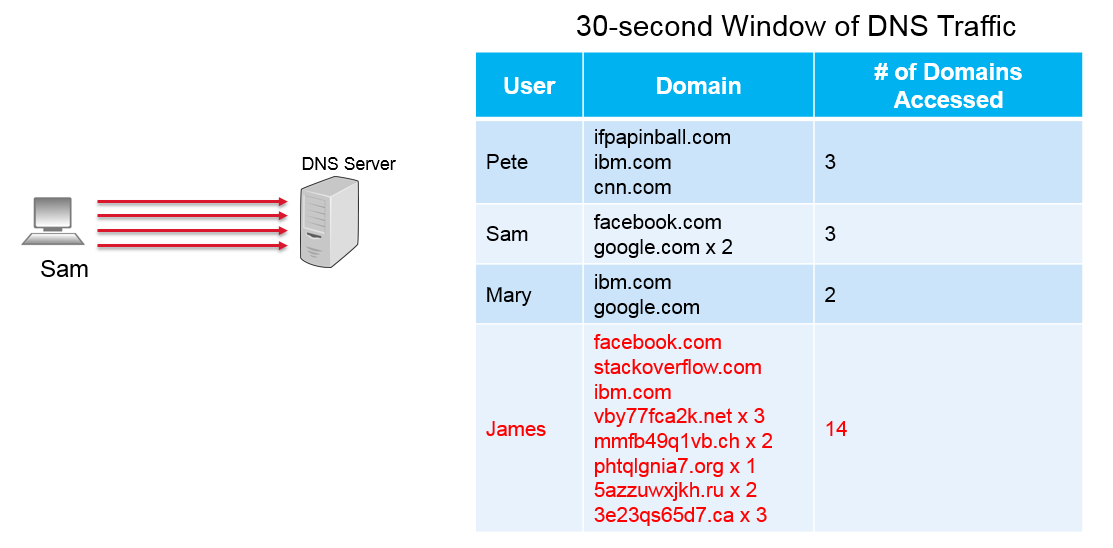

In this scenario, a 30-second window of DNS response traffic was captured. Using this information, a profile was built for each unique user. As part of that profile, the domains that were accessed and the number of times a domain was accessed were captured. This scenario will be referred to as the “normal” or “expected” behaviour of the network. Each user accessed a couple of domains over the course of 30 seconds. In this case, there is nothing out of the ordinary and the operator will report that each of the users is “benign”. Now let’s look at another scenario.

Once again, the above scenario represents a 30-second window of DNS response traffic. However, after building a profile for each user, a clear anomaly is present. The James user accessed 8 different domains 14 times over the course of a 30 second window. Compared to the other users who only accessed 2 or 3 domains, this behaviour is unusual and the HostProfiling operator would report this user as “suspicious”.

Similar to the DomainProfiling use case, this example is intended to illustrate the high-level approach that the HostProfiling analytics use to determine whether a user (or system) is behaving suspiciously. In an actual application, preprocessing of the DNS traffic needs to occur prior to being analyzed by the operator.

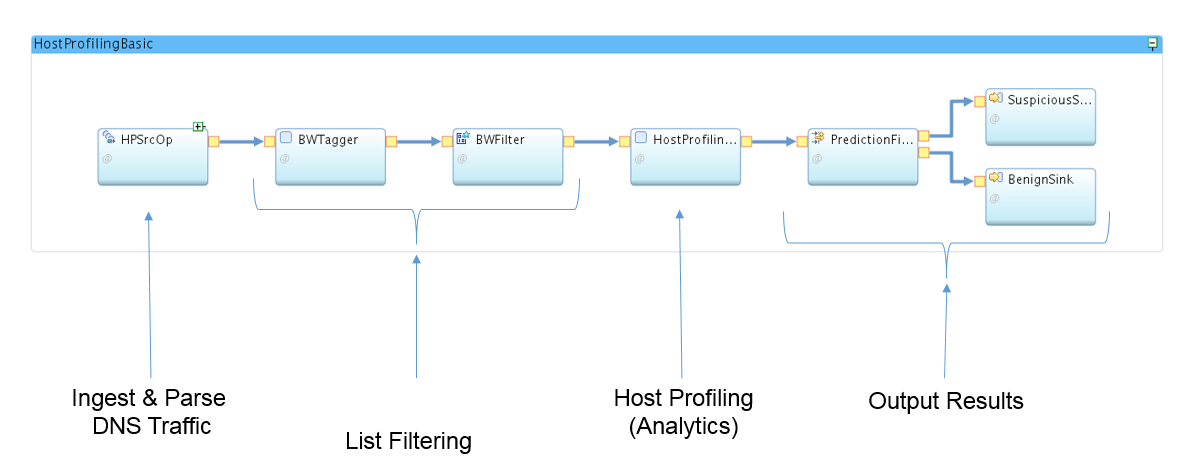

Here is a breakdown of the different parts of the HostProfilingSample application:

Predictive Blocklisting

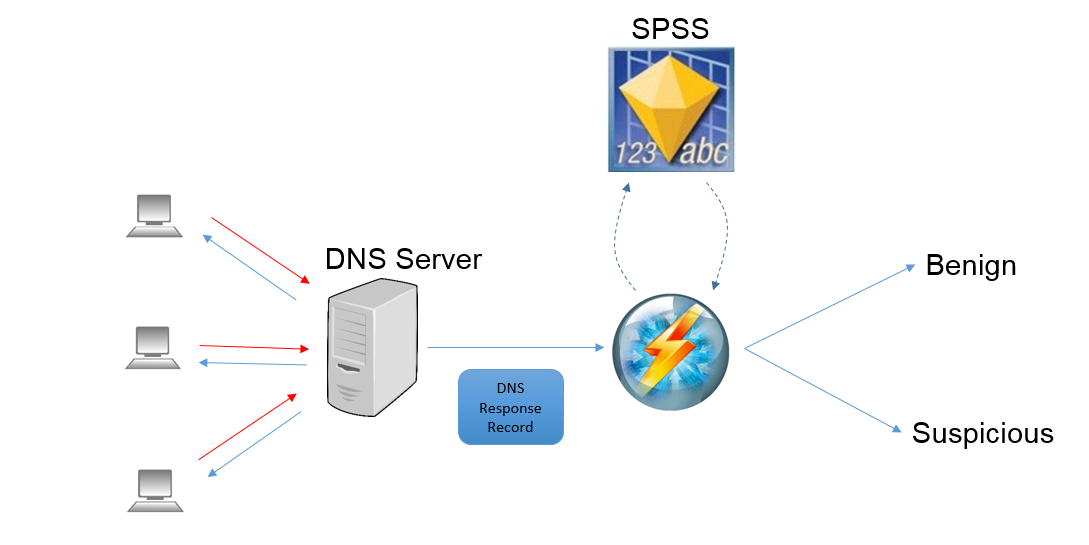

The PredictiveBlocklisting operator uses a pre-built SPSS model to analyze DNS traffic and predict whether a domain should be added to a blocklist. This is done by analyzing the characteristics of the DNS response records, calculating a feature vector and then using an SPSS model to score the record and make a prediction.

In order to use this operator, SPSS Modeler Solution Publisher must be installed on the Streams cluster. After analyzing a DNS response record, the PredictiveBlocklisting operator will return a value of either “benign” or “suspicious”. Suspicious domains should be considered for inclusion in internal blocklists.

The PredictiveBlocklisting operator can be an extremely effective tool to help prevent systems from accessing malicious domains. By using the PredictiveBlocklisting operator, companies can gain the edge in determining which domains should be blocklisted. In many real-world use cases, this model has been able to predict suspicious domains days and weeks before other public and subscription-based blocklist are updated.

Like the DomainProfiling and HostProfiling operators, the PredictiveBlocklisting operator requires a specific set of filters and enrichments in order to work properly.

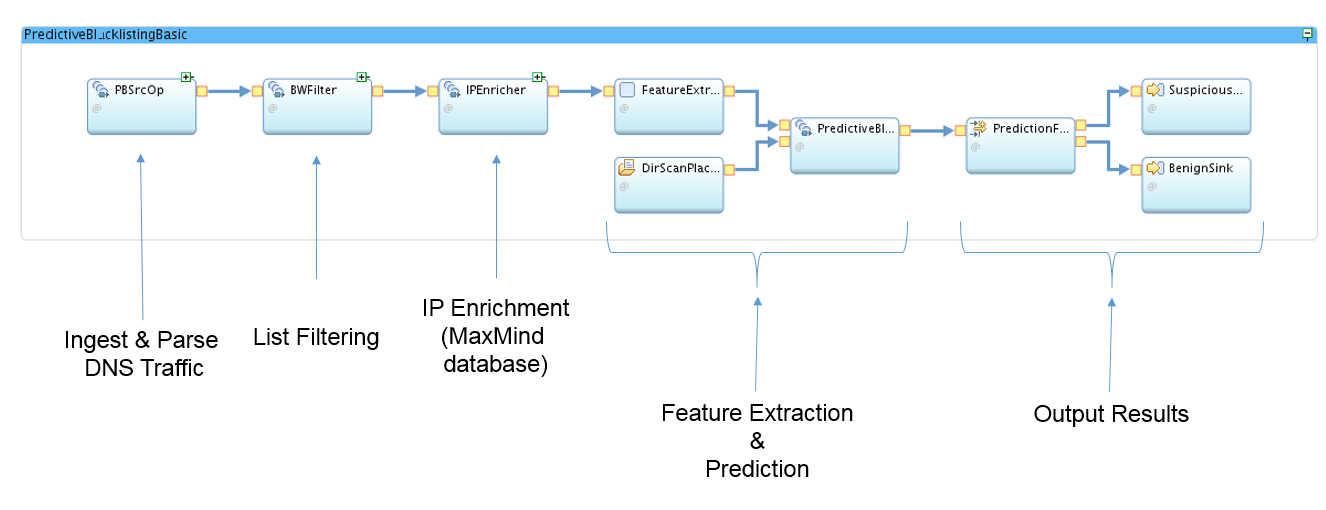

Here is a breakdown of the different parts of the PredictiveBlocklistingSample application:

Ingesting Data

The starter applications described above use the PacketFileSource operator to read a packaged, sample PCAP file. This is useful for validating that the applications and operators work as expected. However, once this validation is complete, users will want to test these applications on their real network data. There are a few different approaches that can be used to ingest real network data.

Live Network Packets (over-the-wire)

This is the best approach for analyzing network traffic in real-time. The com.ibm.streamsx.network toolkit contains an operator called PacketLiveSource. This operator is capable of capturing live network packets from an Ethernet interface. In the starter applications, the PacketFileSource operator can be replaced with the PacketLiveSource operator. These two operators have a very similar API in terms of output functions and parsing the packet headers. The are many samples in the streamsx.network repository on GitHub that demonstrate how to configure the PacketLiveSource operator. Once this operator has been placed into the applications, the next step will be getting the DNS packets mirrored to one of the hosts in the Streams cluster. This step may require special configuration within your network and should be performed by a network administrator.

PCAP Recording

In some environments, it may not be possible to mirror the DNS packets to a host in the Streams cluster. In this case, it may be necessary to store the packets on disk in PCAP recording files. This approach can also be used to perform testing and debugging of an application using a consistent set of input data. To implement this approach, a DirectoryScan operator should be connected upstream of the PacketFileSource operator. The DirectoryScan operator should be configured to scan the directory that contains the PCAP files.

Log Files

In some cases, DNS traffic data may be stored in log files. The starter applications can be modified to work with log files as well, however this approach will require special handling. First, the log files must contain all of the necessary data to populate the attributes of the schema on the output port of the DNSMessageParser operator. If all of this data is available in the logs, then the PacketFileSource and DNSMessageParser operators will need to be replaced with ingest and parse operators specific for the log file being ingested.

Analyzing Results

The starter applications output the results of the findings to two CSV files: one for benign data and one for suspicious data.

By default, the output of the models is fairly straightforward. Either a domain is classified as “suspicious” or it is classified as “benign”.

The output of these models can be greatly enhanced by correlating this data with additional input sources.

For example, the DomainProfiling starter application contains an example of how to create a list of the unique IPs (hosts) that accessed the domain within the window. By using an additional input source (for example, a DHCP log record) you can determine the specific MAC addresses that the IPs were assigned to during the time that the profile was created.

Conclusion

One of the biggest challenges that organizations face is defending against all of the different forms of cyber attacks. In order to ensure coverage of all of the different possible types of attacks, companies need be agile and able to quickly adopt new techniques and technolgies. Furthermore, any technologies put in place to detect cyber attacks need to be scalable and able to adapt to the ever-changing cybersecurity culture. By using the IBM Streams platform, organizations will get the scalability and flexibility needed out-of-the-box. The Cybersecurity Toolkit in IBM Streams provides organizations with the ability to adapt to new threats and to protect their network on an on-going basis.